In this bi-weekly series reviewing classic science fiction and fantasy books, Alan Brown looks at the front lines and frontiers of the field; books about soldiers and spacers, scientists and engineers, explorers and adventurers. Stories full of what Shakespeare used to refer to as “alarums and excursions”: battles, chases, clashes, and the stuff of excitement.

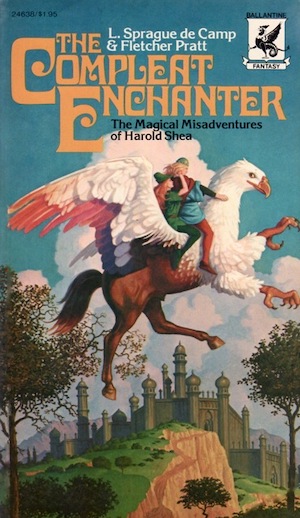

The Compleat Enchanter is a complete delight from beginning to end. The subtitle, The Magical Misadventures of Harold Shea, does a pretty good job of summarizing what occurs: Psychologist Harold Shea discovers a means of using scientific formulae to transport himself to parallel worlds based on myth and fantasy. He can’t always control where he goes, can’t use technology from our world, and has only a sketchy ability to control the magic so common in these worlds. But everyone dreams of being able to jump into the middle of their favorite stories, and Harold Shea is able to do just that. With co-author Fletcher Pratt, L. Sprague de Camp gives us a series of adventures that sparkle with energy and humor—if these two weren’t having a ball when they wrote these, I’ll eat my hat.

I found this book in my basement a few months ago, and said to myself, “These stories were great. It will be fun to revisit them.” But then, when I started reading, I didn’t recognize the stories at all. I doubt that I read and then forgot them, because these are memorable tales. So I think it is more likely that when I purchased this book, probably in my last year of college, it went into the To Be Read pile and never made it out. My impression that these stories were great either comes from reading another of Harold Shea’s many adventures, or from the many positive reviews the stories have received since they first appeared. It’s not the first time my memory has played tricks on me, and at 66 years old, I’m certain it will not be the last.

This collection is not complete, as there are many more adventures of Harold Shea and company (the “compleat” in the title means “consummate,” not “complete”). This particular collection includes three stories—“The Roaring Trumpet,” “The Mathematics of Magic,” and “The Castle of Iron”—which were first published in Unknown, the short-lived fantasy magazine edited by John W. Campbell. Two more tales, “The Wall of Serpents” and “The Green Magician,” appeared separately. Copyright issues prevented all five of the original stories from appearing together for many years, until in 1989, Baen issued them in an anthology (fittingly titled The Complete Compleat Enchanter).

In the 1990s, there were a number of continuations of the series, perhaps spurred by the continuing popularity of the original stories in various collections. Some were written by de Camp alone, while others were written either in collaboration or separately by several other authors, including Christopher Stasheff, Holly Lisle, Roland J. Green, Frieda A. Murray, Tom Wham, and Lawrence Watt-Evans.

About the Authors

L. Sprague De Camp (1907-2000) was a widely respected American author of science fiction, fantasy, historical fiction, and non-fiction. I’ve reviewed work by de Camp before, including his time travel book Lest Darkness Fall, where I included a very complete biography, and the Robert E. Howard collection Conan the Warrior, which he edited.

Murray Fletcher Pratt (1897-1956), who wrote as Fletcher Pratt, was an American author whose non-fiction work, especially his history books, is probably better known than his science fiction writing. He wrote many books on military and naval topics, mainly focusing on the Civil War and World War II, as well as an early work popularizing the field of secret codes. He was known for making historical material feel interesting and lively (I have one of his Civil War books written for younger readers in my own library, given to me during the Civil War centennial, when I was fascinated by the topic).

Buy the Book

The Witness for the Dead

Pratt lived a colorful life. He was a flyweight boxer when young. He started his career as a librarian, but soon moved on to newspaper work and freelance writing. His work also included a time associated with a mail-order writer’s institute, selling entries in biographical encyclopedias, and writing true crime stories. He served as a war correspondent during World War II, which gave him even more material to work with in his history books. He also did pioneering work in naval war gaming, developing a method that used detailed miniatures (of 1/600 scale) and combat calculations that were not based on chance. Upon his untimely death from cancer, the Navy recognized his historical work with their Distinguished Public Service Award.

Pratt’s first story appeared in Amazing in 1928. He began contributing to the pulps, primarily to magazines edited by Hugo Gernsback, writing original stories as well as translating stories from French and German. In addition to the popular Harold Shea stories, Pratt and de Camp wrote the humorous Gavagan’s Bar series. Pratt’s solo fiction books included the fantasy novel The Well of the Unicorn and the science fiction novel Invaders from Rigel (a rather peculiar tale where the few inhabitants of Earth who survive an alien invasion are turned into mechanical robots). He was reportedly very popular among his literary circle of science fiction writers, often hosting parties and regular guests at his home.

While you can’t find any of de Camp’s tales on Project Gutenberg, you can find a few of Fletcher Pratt’s tales here.

Unknown

Unknown was a short-lived, but very influential, fantasy magazine published from 1939 to 1943. It was edited by John W. Campbell, who was the well-established editor of the hard science fiction magazine Astounding, and became a home for tales that did not fit the rigorous standards of its sister publication. At that time, the long-running leader of the fantasy field was Weird Tales magazine, a publication that focused on horror and more lurid stories. Unknown had a more whimsical and humorous approach, and even in its tales of magic, Campbell insisted on rigor and internal consistency in creating magical rules. L. Sprague de Camp and Fletcher Pratt’s Harold Shea stories are a perfect example of the type of tale Campbell was looking for. Unknown is also notable for printing the first tales in Fritz Leiber’s classic Fafhrd and the Gray Mouser series.

Unfortunately, the magazine did not sell well, and wartime paper shortages were apparently a factor in its demise. There were attempts to resurrect it, but none were successful, and many of the stories that might have fit well in Unknown ended up in other magazines, most notably The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, which began publication in 1949. The criteria for stories appearing in Astounding also became a bit looser, with a perfect example being Randall Garrett’s Lord Darcy series, where a detective solved mysteries in a world where the scientific application of magic had taken the place of technology.

The Compleat Enchanter: The Magical Misadventures of Harold Shea

The Harold Shea stories, like many of de Camp’s works, are filled with wry humor. But they also display an added element of whimsy and even slapstick comedy, which I suspect comes from Pratt’s influence. The tales are well rooted in history and the mythology they explore, a testament to the wide-ranging knowledge of the two authors. While they are even more entertaining for readers who know something of the worlds Shea visits, they can be read without any such advance knowledge.

The first tale, “The Roaring Trumpet,” begins with three psychiatrists—Harold Shea, Walter Bayard, and Reed Chalmers—discussing their efforts to define a new field of “paraphysics,” which involves the existence of an infinity of parallel worlds, some of which may include the worlds of myth, fable, and fantasy stories. They suspect that one of the causes of dementia may be the patient’s mind not fully existing solely in our own world, but in one of these parallel worlds as well.

Shea is an active and restless man, always seeking new hobbies, including fencing, skiing, and horseback riding. When the doctors come up with a possible means of transporting themselves to other worlds through the recitation of formulae, he jumps at the chance. While he intends to visit the world of Irish myth, he ends up instead in a world of Norse mythology, on the eve of Ragnarök, the Norse version of the apocalypse. Shea has brought modern tools to aid him, including a pistol and some matches, but discovers that since these devices do not fit the magical rules of the new world, they do not work. Instead, he finds that his knowledge of logic allows him to perform magical feats that would have been impossible in our world. He also learns that his world of adventure is also a world of danger and discomfort.

Shea follows an old man with some ravens to an inn, only to find the man is Odin, ruler of the Aesir. Shea also meets others from the Norse pantheon, including the boisterous but rather thick Thor, the mercurial Loki, and the plucky Heimdall, and becomes involved in their struggles with various giants, dwarves, and other opponents (here my knowledge of Norse mythology, gleaned from the work of noted scholars Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, came in quite handy).

To avoid spoiling any surprises, I won’t recount Shea’s adventures in detail. But I will mention that at one point, he is imprisoned in a dungeon with another prisoner who, every hour, cries out, “Yngvi is a louse.” This is a phrase I have heard from time to time at science fiction conventions, and always wondered about its origin (such phrases represent an early verbal precursor to what we now call memes). And although I couldn’t find it, I am pretty sure that line appeared somewhere in Heinlein’s Glory Road.

In the second adventure, “The Mathematics of Magic,” Professor Chalmers, despite his rather sedentary nature, is inspired by Shea’s Norse adventure and decides to accompany him on his next foray into fantasy. The two of them end up in the world of The Faerie Queene, by Edmund Spenser. While this particular tale is not familiar to me, I have read many of the tales of chivalry it inspired. The adventurers are soon captured by the plucky, blonde female knight Lady Britomart (and while George R.R. Martin has never verified the connection, many fans have pointed out the resemblance of this character to Lady Brienne of Tarth from Game of Thrones).

There is a league of evil magicians attempting to undermine the forces of chivalry, and Shea and Chalmers decide to infiltrate their ranks and undermine their efforts from within the organization. And along the way the two fall in love—Chalmers with a magical creation named Florimel, and Shea with a Robin-Hoodish forest-dwelling redhead named Belphebe. In the end, to Shea’s delight, Belphebe ends up traveling home with him when he returns to our world, and they marry. Chalmers, however, because his Florimel could not exist in our world, chooses to remain. This story, full of humor, romance, reversals and adventure, was my favorite of those in the collection.

The third story, “The Castle of Iron,” is quite a bit longer than the first two, and not quite as taut a tale. It also involves more characters, and two settings I am not familiar with, the first being Xanadu from Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s poem Kubla Khan, and the second being the castle from Orlando Furioso by Ludovico Ariosto. Chalmers attempts to contact Shea, but instead pulls first Belphebe, and then Shea, into the worlds of myth. In the world of Orlando Furioso, Belphebe inhabits the similar character of Belphegor, and entirely forgets her life and marriage to Shea.

In addition to Shea, fellow psychologist Vaclav Polacek is pulled into the world of fantasy, and has a number of adventures where he is transformed into a werewolf. Since this story involves clashes between Muslims and Christians, I was worried there might be material offensive to modern readers. But while the characters display prejudices, the authors take a very even-handed approach to the religious conflicts. Chalmers is motivated by his desire to transform his beloved Florimel from a creature of magic into a real woman, but is in quite over his head. The best part of the book is a long and convoluted quest that Shea undertakes with Belphebe/Belphegor, while having to deal with her new boyfriend, an extremely selfish and cowardly minstrel. The tale, like the others, has a happy resolution, but for me, it would have benefitted from arriving there a bit more directly.

Final Thoughts

These three adventures featuring Harold Shea were absolutely enchanting, if you will pardon the pun. They were exciting, entertaining, and at times, laugh-out-loud funny. They have aged very well, and I would recommend them highly to modern readers.

If you are one of the readers who have encountered these tales before, I would love to hear your impressions. And there are a lot of other stories out there in this same vein, which transport their protagonists to worlds of myth and story—if you have other favorites, I would enjoy hearing about them from you.

Alan Brown has been a science fiction fan for over five decades, especially fiction that deals with science, military matters, exploration and adventure.